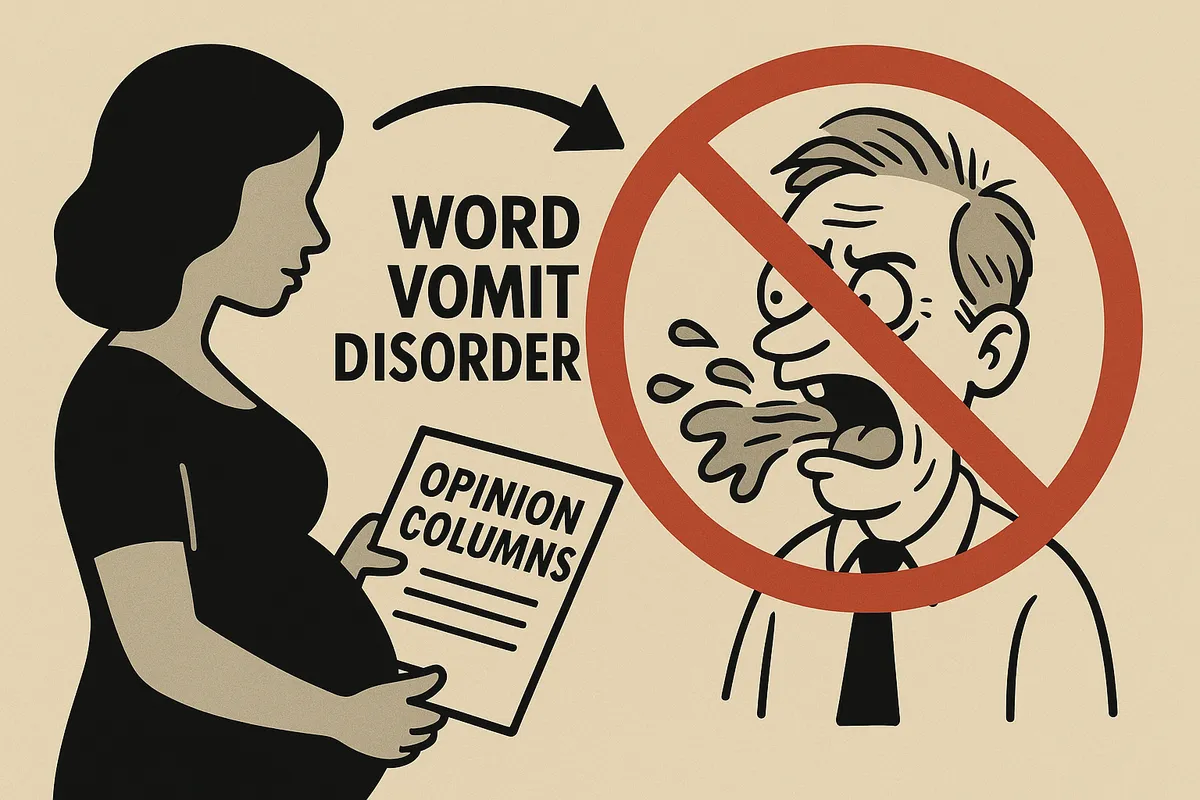

Word Vomit Disorder: How Ronald L. Hirsch Discovered a New Epidemic

A reminder that confidence is not a credential

A reminder that confidence is not a credential

Rates of Word Vomit Disorder (WVD) have doubled every decade since the rise of dial‑up. Once confined to late‑night talk radio and unmoderated comment sections, the disorder now affects one in every thirty‑one pundits. Experts suspect a link between the overproduction of opinions and the gradual decline of critical literacy. One name has become central to the conversation: Ronald L. Hirsch, who recently proposed that social media use in pregnant women causes autism. His hypothesis may not have reshaped neuroscience, but it has done wonders for the early detection of WVD.

The condition typically manifests as a compulsive need to draw sweeping conclusions from coincidental data. Sufferers often exhibit inflated self‑confidence paired with resistance to common sense. In mild cases, symptoms include the urge to compare correlation with causation; in severe cases, the patient begins publishing op‑eds. Hirsch’s case appears to be of tragic proportions. He observed that autism rates and internet use rose during the same decades, then diagnosed an entire population from the comfort of a keyboard.

To be fair, Hirsch isn’t alone. The Center for Unsubstantiated Discourse (CUD) reports that rates of unqualified commentary have risen in lockstep with broadband access. Pew Research estimates that by 2015, 65 percent of adults were connected to the internet — and nearly all of them were convinced they could outthink epidemiologists. While this data doesn’t prove causation, it does prove irresistible to those afflicted with WVD.

Like most behavioral epidemics, Word Vomit Disorder often begins in isolation. Extended exposure to one’s own reflection — or to sympathetic comment threads — can trigger the first episode. Untreated, it progresses to full‑blown irresponsibly flawed punditry, characterized by anecdotal reasoning, moral panic and the belief that motherhood is always to blame. Hirsch’s article checks every diagnostic box. He even prescribes behavioral abstinence for pregnant women, as if scrolling Instagram were a gateway drug to neurodivergence.

Public health authorities have yet to issue official guidelines, but early interventions show promise. Experts recommend limiting daily output to one opinion per twenty‑four hours and supplementing with peer‑reviewed reading. In high‑risk individuals, direct contact with autistic people or actual data may trigger remission.

There are no confirmed fatalities from Word Vomit Disorder, though many conversations have died of exhaustion. Still, the threat remains real. As Hirsch himself might say, we cannot ignore the coincidence. The rise in amateur expertise aligns perfectly with the proliferation of “publish” buttons. And until further research clarifies whether writing without knowledge directly causes harm, prudence demands prevention.

If Ronald L. Hirsch’s essay teaches us anything, it’s that the human mind craves pattern, even when meaning isn’t there. It also teaches us that the internet is not responsible for autism — but it might be responsible for the spread of Word Vomit Disorder. Until a cure is found, the best defense is skepticism, hydration and closing the tab before the next outbreak begins.