When the Brain Learns to Pass

What new research reveals — and conceals — about autistic adolescents who don’t “seem autistic”

What new research reveals — and conceals — about autistic adolescents who don’t “seem autistic”

A new study out of Drexel University and Stony Brook offers a glimpse into a familiar — and often misunderstood — phenomenon: autistic adolescents who appear less autistic in everyday life than they do in clinical settings.

The term the researchers use is PAN: Passing As Non-autistic. And while that phrase might sound performative — a matter of effort or intent — the data suggest something deeper.

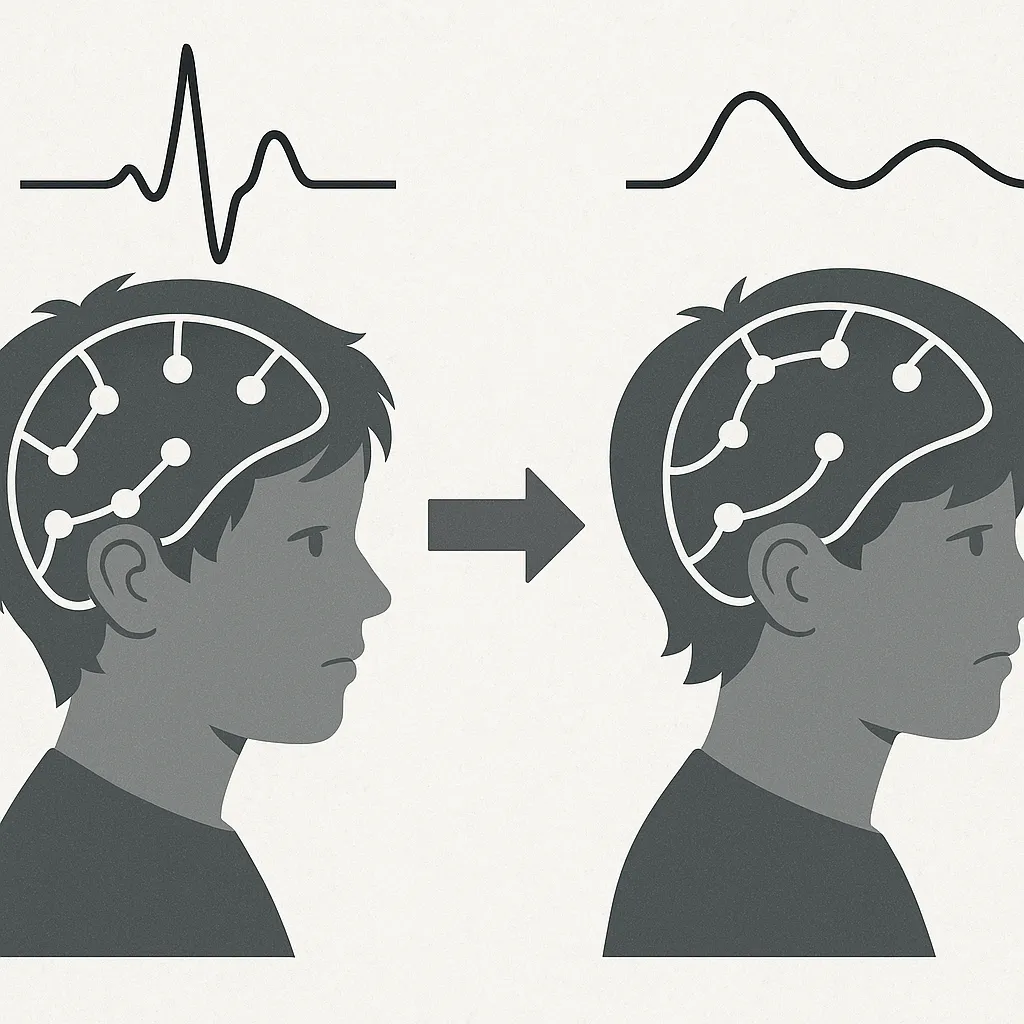

The study measured brain activity using EEG while teens viewed emotional facial expressions. It focused on two known markers of social processing:

- N170 latency, which reflects automatic face recognition

- LPP amplitude, which reflects emotional reactivity

Here’s what they found:

- Teens who met criteria for autism during clinical evaluation but were rated as “less autistic” by parents or teachers showed faster N170 responses — suggesting quicker recognition of faces

- They also showed dampened LPP responses to subtle emotions — suggesting reduced reactivity to ambiguous social cues

In plain terms: these teens processed faces more efficiently and reacted less strongly to them — at least neurologically.

They weren’t told to mask. They weren’t practicing scripts. They were sitting alone in a lab, watching faces flash on a screen.

And yet their brains told a story of adaptation.

PAN Is Not a Choice — It’s a Conditioned Pattern

Over time, autistic teens may learn — consciously or unconsciously — that certain responses invite scrutiny, while others go unnoticed or accepted

This study doesn’t ask teens how they feel. It doesn’t measure stress, masking behavior or burnout. It doesn’t investigate why PAN happens — only that it correlates with different neural patterns.

But those patterns matter. Because they suggest that “passing” isn’t always about pretending. Sometimes, it’s about perception. Sometimes, it’s about your nervous system learning — over years — what happens when you respond “too much,” “too oddly” or “too real.”

What this study shows is that the brain itself may begin to blunt that response.

Not as rebellion. As survival.

What the Study Gets Right — and What It Misses

This is careful work. It avoids pathologizing language. It names masking and camouflaging without romanticizing them. It uses informant discrepancies — between parent, teacher and clinician reports — as a signal that context matters.

That’s rare and valuable.

But what’s missing is just as important.

There are no autistic co-authors. No inquiry into internal experience. No engagement with what this pattern costs the teens who live it.

When a teen’s brain shows faster recognition and lower reactivity, we don’t know if that means they’re thriving — or just expertly hidden. We don’t know if that dampened LPP reflects emotional control, emotional exhaustion or emotional absence. We don’t know if that “efficiency” is peace or pressure.

What we do know is that teens who PAN are often the ones missed by systems built to notice distress.

And when your support depends on visibility, invisibility becomes a trap.

This Isn’t a Warning. It’s a Mirror.

To educators, clinicians and researchers who still equate low “observable symptoms” with low support needs: this study is a mirror. Look at it.

Because the teens who pass? They’re not proof that autism is overdiagnosed. They’re evidence that your filters are flawed.

And the longer they go unseen, the harder it gets to tell adaptation from harm.

Let this study be a start — not just of measuring PAN but of listening to those who live it. Not just EEGs and discrepancy scores but stories, stress and selfhood.

Because passing isn’t the opposite of being autistic.

It’s the consequence of being expected not to be.

Study citation:

Houck, A.P. et al. (2025). Automatic and affective processing of faces as mechanisms of passing as non-autistic in adolescence. Scientific Reports. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-025-04801-y