Pollution Becomes an Autism Metaphor

How a Student Paper Turned Autism Into Fallout

How a Student Paper Turned Autism Into Fallout

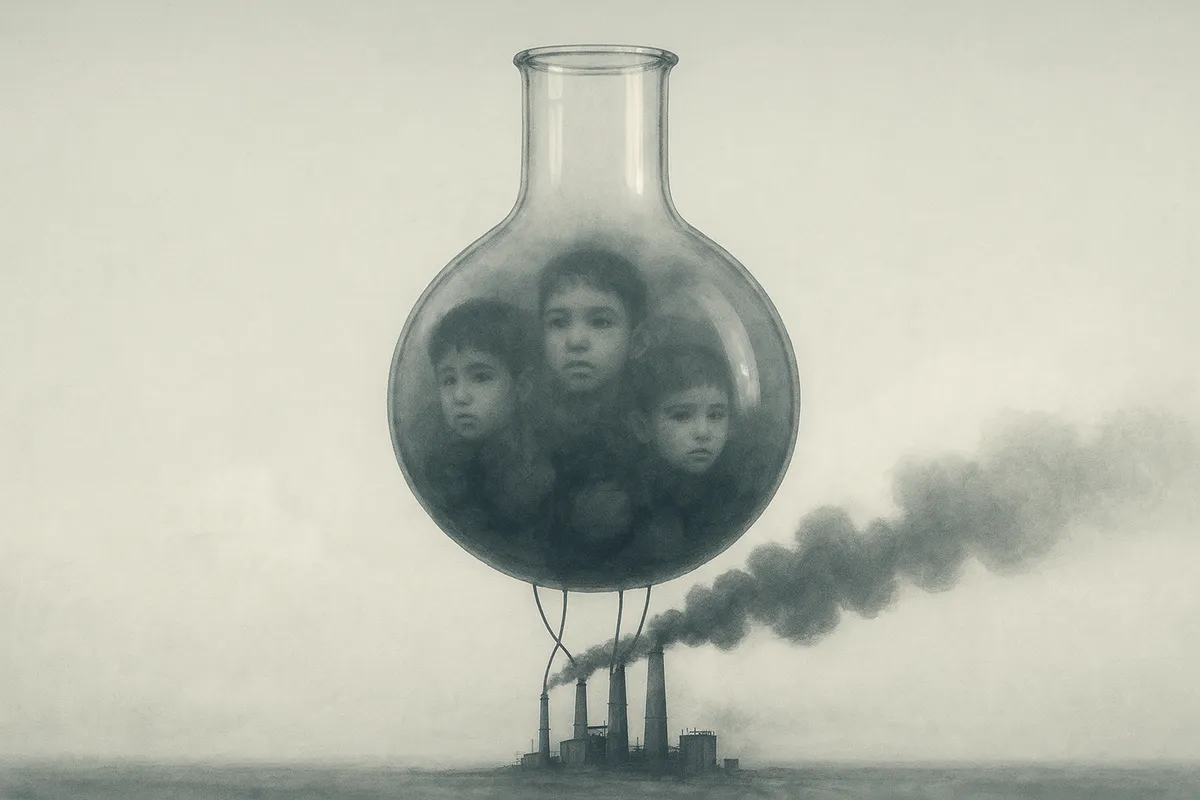

I recently ran across a University of Baghdad research project titled Autism in the Air: From Lead Oxide Exposure to the Development of Autism Spectrum Disorder. It is so flawed that it makes me wonder whether RFK Jr. was a project consultant. Granted, these are undergraduate research trainees, but the authors propose that lead oxide exposure might cause autism, citing oxidative stress and altered gene expression. The story underneath the hypothesis is much older and still false: autism as contamination, and autistic people as proof that the air itself has gone bad.

The Frame: Autism as Pollutant

The study begins with a familiar deficit arc. Lead oxide is described as a neurotoxin, autism as its outcome, and autistic children as casualties of industrial neglect. The language is not merely speculative; it is moralizing. The authors warn that lead exposure could cause “irreversible physical and mental abnormalities” that might spread “throughout mankind.” The harm is structural, not stylistic — it reframes an identity as evidence of societal failure.

This is not an innocent misstep in translation. Framing autism as the symptom of pollution turns environmental policy into population control. When a condition becomes a warning sign, the people who live with it become the warning itself. That is the point where science begins to echo eugenics, even when no one says the word aloud.

The study begins with a familiar deficit arc. Lead oxide is described as a neurotoxin, autism as its outcome, and autistic children as casualties of industrial neglect. The language is not merely speculative; it is moralizing. The authors warn that lead exposure could cause “irreversible physical and mental abnormalities” that might spread “throughout mankind.” Autism is positioned not as human variation but as a preventable disease. The harm is structural, not stylistic — it reframes an identity as evidence of societal failure.

This is not an innocent misstep in translation. Framing autism as the symptom of pollution turns environmental policy into population control. When a condition becomes a warning sign, the people who live with it become the warning itself. That is the point where science begins to echo eugenics, even when no one says the word aloud.

The Method: A Study That Already Knew Its Answer

The paper is an undergraduate project — a student exercise that reveals how harmful frames can enter professional training — but the logic mirrors larger academic habits. It relies on a convenience sample of fifty people with autism drawn from a single institution. There is no control group, no measure of lead exposure, and no ethical reflection on consent or participation. Yet it concludes that “elevated lead concentrations may play a pathophysiological role” in autism — a claim far beyond its data.

Methodological weakness becomes narrative strength only when the frame demands it. The authors were not asking whether autistic people face higher lead exposure. They were asking whether lead causes autism. The outcome was written before the analysis began.

The Rhetoric: Science as Salvation

The paper ends with a plea to “reverse climate change” and prevent a spread of “mental abnormalities.” The logic collapses environmentalism into purification — a clean planet measured by the absence of people like us. It mistakes solidarity with fear. The idea that protecting children means preventing autism is not science; it is superstition with data tables.

Even within an educational context, the issue points to systems more than individuals — the teachers who approve these projects, the curricula that reward compliance, the research culture that frames autism as pathology ... all this matters. When students are taught to treat autism as contamination, they are being trained in a moral hierarchy, not medicine. The harm travels forward, shaping how future physicians will diagnose, treat and speak.

What Real Questions Would Look Like

If the goal were truly public health, the study could have asked something else: Do autistic people face higher environmental burdens because of poverty or infrastructure? Are sensory sensitivities worsened by air pollutants? How do policy failures intersect with disability? Each question preserves autistic life as worth studying, not erasing.

Why This Still Matters

Every generation rediscovers a new toxin to blame. Lead, mercury, vaccines, Wi-Fi — the medium changes, the metaphor remains. What these stories share is not chemistry but control: the wish to keep autism elsewhere, caused by something foreign, fixable and not us. That fantasy comforts the powerful, and their acolytes. It does not clean the air.

The harm here is not only factual; it is ontological. When autism is cast as fallout, autistic people become environmental damage. And when research carries that metaphor forward, it does not protect humanity. It just redraws its borders.