When Aggression Becomes a Diagnostic Biomarker

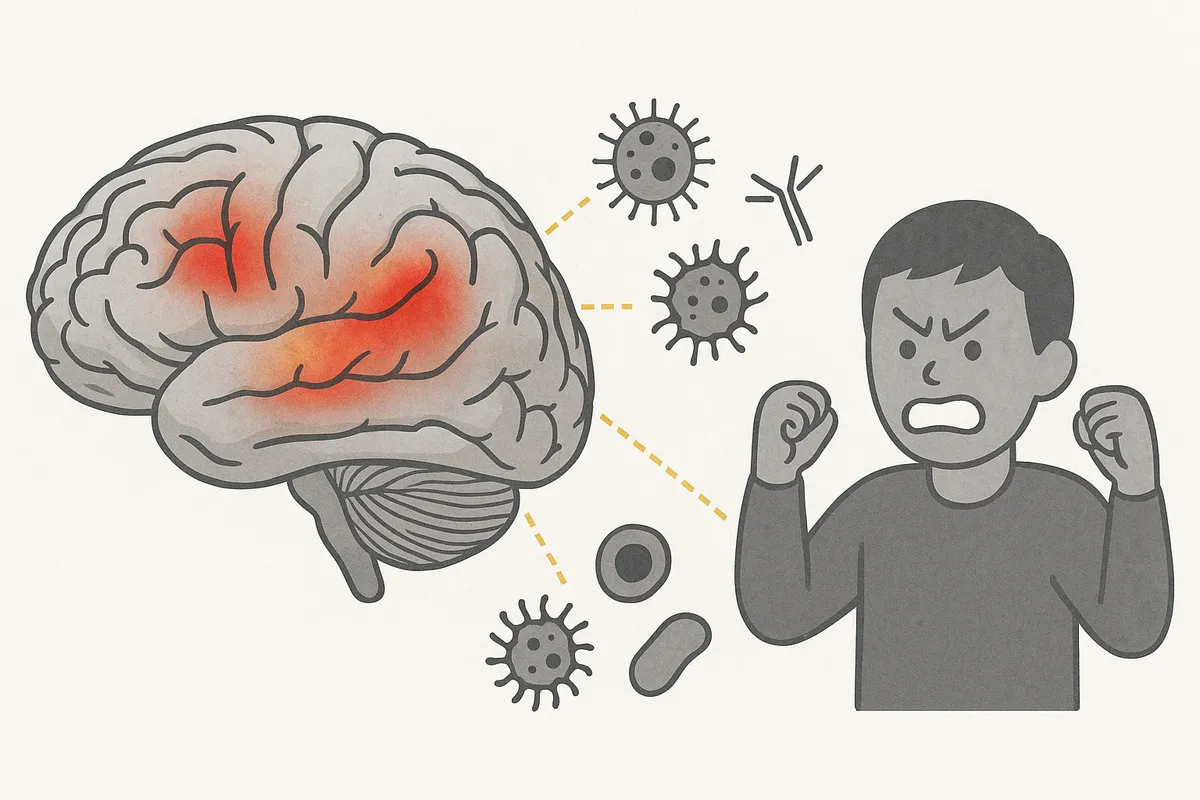

In July 2025, the journal Brain, Behavior and Immunity published a study titled: "Multimodal associations between brain morphology, immune-inflammatory markers, spatial transcriptomics and behavioural symptoms in autism spectrum disorder." Its goal? To link aggression in autistic individuals to immune and inflammatory signals, MRI-based brain morphology and spatial gene expression maps.

In July 2025, the journal Brain, Behavior and Immunity published a study titled: "Multimodal associations between brain morphology, immune-inflammatory markers, spatial transcriptomics and behavioural symptoms in autism spectrum disorder." Its goal? To link aggression in autistic individuals to immune and inflammatory signals, MRI-based brain morphology and spatial gene expression maps.

Its result? A familiar narrative wrapped in sophisticated data.

Researchers sorted autistic participants into two groups based on levels of aggression then scanned their brains, measured immune markers in their blood and layered the findings with gene expression data from brain atlases. They reported correlations between higher aggression and elevated inflammatory markers (like TNF-α and IL-6) alongside changes in cortical thickness and structural alterations in specific brain regions.

The conclusion? That aggression in autism may reflect a distinct immune-related biological subtype with possible implications for treatment.

But before this study is heralded as a breakthrough, let’s pause. Not because the data isn’t interesting but because the frame is flawed.

The Framing Problem: Aggression as a Symptom

Aggression is real. So is distress. But this study treats both as internal biological failures. Nowhere in the paper is aggression framed as communication or as a response to an inaccessible or overwhelming environment. Nowhere do the authors ask: What role does trauma, sensory overload or unmet support needs play?

Instead, aggression is reduced to a marker of biomedical severity — something to be measured, mapped and ultimately medicated.

We’ve seen this before.

It’s the same logic that built the compliance-based therapies autistic people have spent decades resisting. The same logic that says a distressed child is disordered rather than dysregulated. That a self-injurious teen needs inflammation suppression, not safety and dignity.

Multimodal Data, Monomodal Ethics

This study pulls from many data sources — neuroimaging, cytokine profiles, gene expression maps. But it doesn’t pull from autistic lives. There are no autistic co-authors, no evidence of participatory design, no reflexivity about how aggression is defined, interpreted or pathologized.

Aggression becomes a biomarker.

But aggression isn’t a trait. It’s a moment. A signal. A protest. Sometimes it’s survival.

When researchers treat it as a symptom of a defective brain, they miss the point. And worse, they risk paving the way for interventions that erase behavior without addressing the conditions that cause it.

Risk Without Consent

Autistic people have lived through the consequences of this framing. We know what happens when "problem behaviors" are studied without asking what those behaviors are protecting us from. We’ve seen how risk language leads to restraint, to medication, to institutionalization.

So when a study uses terms like "burden," "severity," or "dysregulation," we listen carefully.

Because we know: the next study might use those findings to justify suppressing the people they describe. Not through understanding but through force.

What Could Have Been Different?

This could have been a powerful inquiry. What if the authors had asked autistic people what aggression feels like? What leads to it? What helps? What if they had framed the immune findings not as causes of bad behavior but as physiological reflections of stress, trauma and overload?

What if they had asked: What does the biology of distress look like when the world never makes room for your brain?

That’s not speculation. That’s science with a spine.

Final Thought

This paper will likely influence future autism research. Its methods are rigorous. Its findings are eye-catching. Its funding, I suspect, is secure.

But rigor without ethics is not progress. And insight without inclusion is not safety.

Aggression should never be ignored. But before it becomes a biomarker, it must be understood. Because when the goal is to reduce visible signs of distress without asking what that distress is trying to say, we’re not treating autism. We’re silencing it.

And autistic people deserve better than silence.