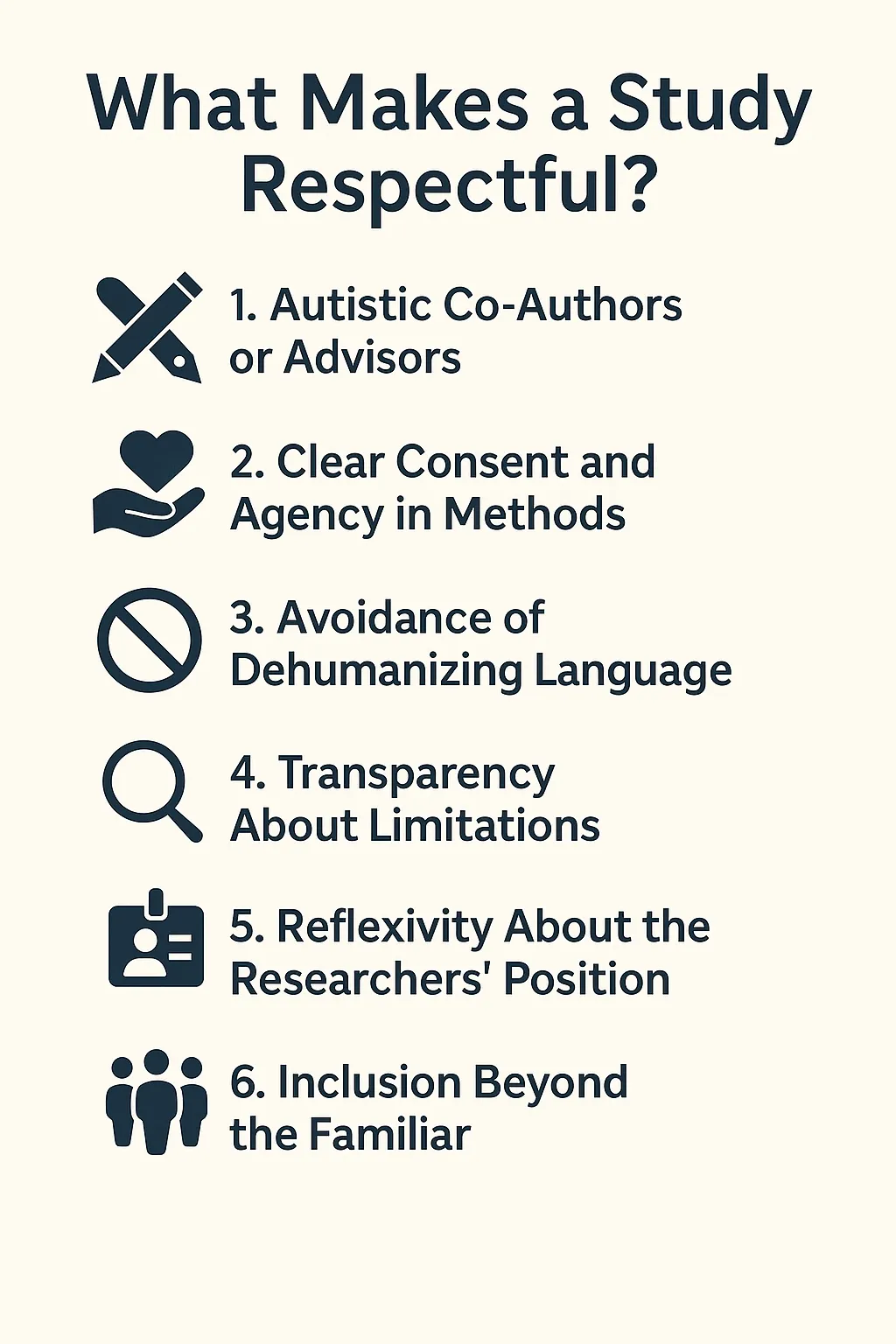

What Makes a Study Respectful?

I’ve been thinking a lot about what separates a research study that merely mentions autistic people from one that truly respects us.

Not all harm comes from bad intentions. Sometimes it comes from habits — from default assumptions about who gets to ask the questions, and who exists only as the data.

So here’s a working list. Not a checklist. Not a purity test. Just a set of signals I’ve come to notice when reading autism research. Signals that suggest a study might actually be worth engaging with — not just critiquing.

1. Autistic Co-Authors or Advisors

This one isn’t optional anymore. If a study is about us — our development, our experience, our cognition — and we’re not listed anywhere as contributors, something’s wrong.

You don’t have to speak for us if you speak with us.

Even an advisory role — cited clearly, not buried — can shift the center of gravity in the work. It signals that researchers are listening not just to data, but to people.

2. Clear Consent and Agency in Methods

Was participation voluntary? Were communication needs respected? Did participants know how their data would be used?

This matters especially when working with children or non-speaking individuals. Consent isn’t just about forms — it’s about power.

Respectful studies build consent into the design, not just the paperwork.

3. Avoidance of Dehumanizing Language

“Burden.” “Impairment.” “Deficit.” “Problem behavior.” These words still show up — even in studies claiming to be neurodiversity-affirming.

Respectful research doesn’t require euphemisms. But it does require awareness. If the language would sound strange applied to non-autistic people, it probably needs a rethink.

Words shape frames. Frames shape impact.

4. Transparency About Limitations

Every study has limits — sample size, cultural bias, lack of lived experience in the design team. Respectful research says so, plainly.

When limitations are buried, the findings often get treated as universal. That’s how nuance gets flattened. That’s how policies and interventions get misapplied.

Naming what a study can’t claim is a form of humility. It’s also a kind of respect — for the reader, and for the people being studied.

5. Reflexivity About the Researchers’ Position

Who funded the work? What institutional pressures shaped the questions? Where does the lead author stand in relation to the topic — professionally, ideologically, personally?

Most studies don’t say. But some do. And those few feel different. They read like the work of people who know they’re part of the system they’re describing — not floating above it.

Respectful research shows its scaffolding. It names its angle.

6. Inclusion Beyond the Familiar

It’s not just about whether autistic people are included. It’s about which autistic people are included.

Often, research teams will list a contributor with lived experience — but that contributor tends to be verbal, academically fluent, institutionally comfortable. In short: someone researchers already know how to talk to.

This kind of inclusion is easier — and safer — for the system. But it risks flattening the spectrum and reinforcing the idea that only certain autistic voices are “usable.”

Respectful research makes space for those with different communication styles, higher support needs, or lived experiences that don’t fit easily into the research pipeline. That’s slower work. But it’s also deeper, more honest work. Anything less is still exclusion — just with better branding.

A Living Lens

This list isn’t final. It will change as I read more, learn more, listen more. But I wanted to offer it as a lens, not a law. A way of seeing that invites readers — especially autistic readers — to ask better questions of the research that claims to speak about us.

Because too often, the science moves fast, the language moves past us, and the stakes are left unnamed.

Respect starts in the design. But it also shows in the details.