The "Broken Wiring" Story Returns — This Time in RNA

Difference doesn’t equal defect — it depends on the lens

Difference doesn’t equal defect — it depends on the lens

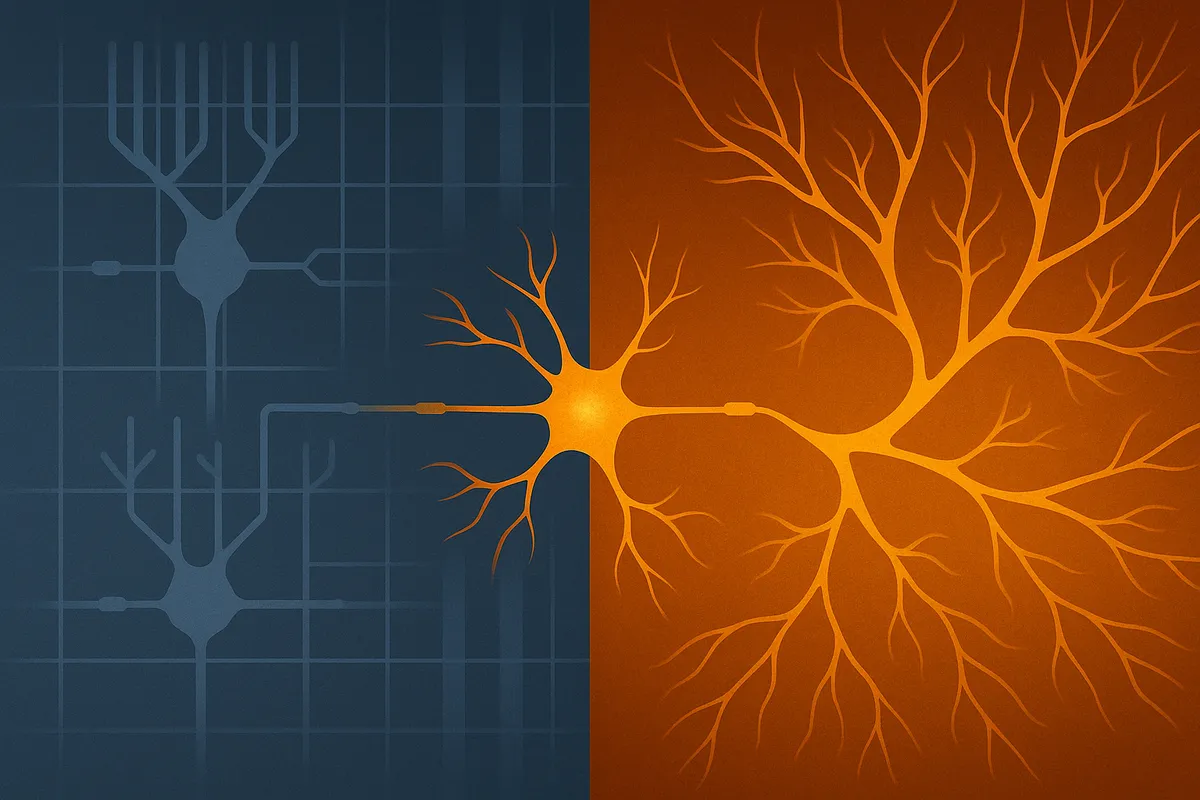

PsyPost’s August 15 coverage of a UCSF study, republished from The Conversation, promises a revelation: "New technology reveals how autism disrupts brain cell communication." Lead author Dmitry Velmeshev, using single-nucleus RNA sequencing on postmortem brain tissue, describes RNA-level differences in specific neuron types and frames them as defects to be repaired. The article is rich in technical detail but thin on perspective. No autistic people are quoted, no ethical debate is invited and no alternative interpretations are offered. The conclusion — that autism is a disease of broken synapses in need of repair — is not an inevitable reading of the data. It’s a choice of frame shaped by the norms, incentives and defaults of biomedical science.

Where the Harm Takes Root: The harm isn’t in sequencing brain cells — it’s in the reflex to treat deviation from the neurotypical control group as malfunction. In biomedical neuroscience, this reflex is reinforced by training that equates difference with disease, funding structures that reward “repair” language and journals that expect pathology-driven narratives. That doesn’t mean all researchers consciously choose this frame, but the system makes it the path of least resistance. In many cases, pathology-driven narratives overshadow — and in some ethical arguments, undermine — strengths-based or adaptive-function research, because pursuing both in parallel risks framing identity-linked traits as assets in one breath and defects in the next. This duality can send mixed signals to participants and the public, raising questions about whether it is truly possible to pursue both without conflict. By omitting autistic perspectives the work forfeits an opportunity to interrogate these assumptions, leaving readers with the idea that the only good autistic brain is one made to look neurotypical.

What the Data Showed: Researchers analyzed brain cell nuclei from autistic and non-autistic people after death using advanced RNA sequencing techniques capable of examining individual nuclei. They found RNA differences in upper-layer cortical neurons, which connect different brain regions, and in glial cells, which support neuron function. These were interpreted as malfunctions that may cause autism, especially in nonspeaking individuals. While such consistent correlations can be valuable leads for causal research, presenting them only as defects narrows interpretation. That framing may resonate with some who want medical intervention — and wanting symptom relief is not incompatible with valuing neurodiversity — but it’s still only one lens. The same data could also be seen as evidence of distinctive processing architecture shaped by both innate wiring and lived experience.

How the Frame Operates: Set: Neurotypical brain structure is treated as the unquestioned baseline. List: Autism is labeled a "disease"; synaptic differences are called "malfunctioning"; relief is imagined only through biomedical repair. Land: Pathology-driven narratives can, and often do, overshadow inquiry into autistic strengths, resilience or environmental influences — though some labs claim to pursue both, prompting ongoing ethical debate about whether such dual framing can avoid undermining either goal.

Who Gains From This Narrative: Mechanism: Persistent deficit framing pathologizes difference at the cellular level, conflates correlation with causation and sidelines any interpretation that doesn’t lead to a cure. Beneficiary: Biomedical research pipelines, institutions and — in some cases — pharmaceutical companies whose funding models depend on identifying and fixing defects. The bias here can be systemic rather than deliberate, but its effects are the same.

Gaps in Method and Context: Postmortem samples reveal associations, not causes. In neuroscience, such associations are often positioned as plausible mechanisms to secure further study. But the leap from “possible mechanism worth testing” to “repairable defect” is not required by the data — it’s encouraged by grant language, publication norms and media translation. Between paper, press release and PsyPost rewrite, nuance is lost and pathology becomes the headline. Researchers who want to preserve complexity must actively counter that drift.

A Direct Appeal to Dr. Velmeshev: Your methods are powerful. They could illuminate how diverse brains adapt, reorganize and thrive in different environments — not just how they deviate from a neurotypical template. The same precision tools you’ve used to map difference could explore function without presuming pathology. In a field crowded with cure narratives you have the credibility to show that molecular neuroscience can ask richer questions and still be taken seriously by peers and funders. That shift would not weaken the science — it would expand it.

Questions That Need Asking:

- Could these RNA differences reflect autistic processing styles rather than defects?

- How might chronic stress from living in a hostile environment influence gene expression?

- What ethical guardrails exist to prevent identity-erasing interventions?

- How could participatory research alter the interpretation of these findings?

Closing Challenge: When autism is only ever read as circuitry to be repaired the science becomes a tool for narrowing human possibility rather than expanding it. The real breakthrough will come when molecular insights are paired with frameworks that can hold difference without reflexively labeling it broken — and when researchers use their position to resist the defaults that make that labeling seem inevitable.