Study on Acupuncture and Music Therapy Clears Fog but Leaves the Frame

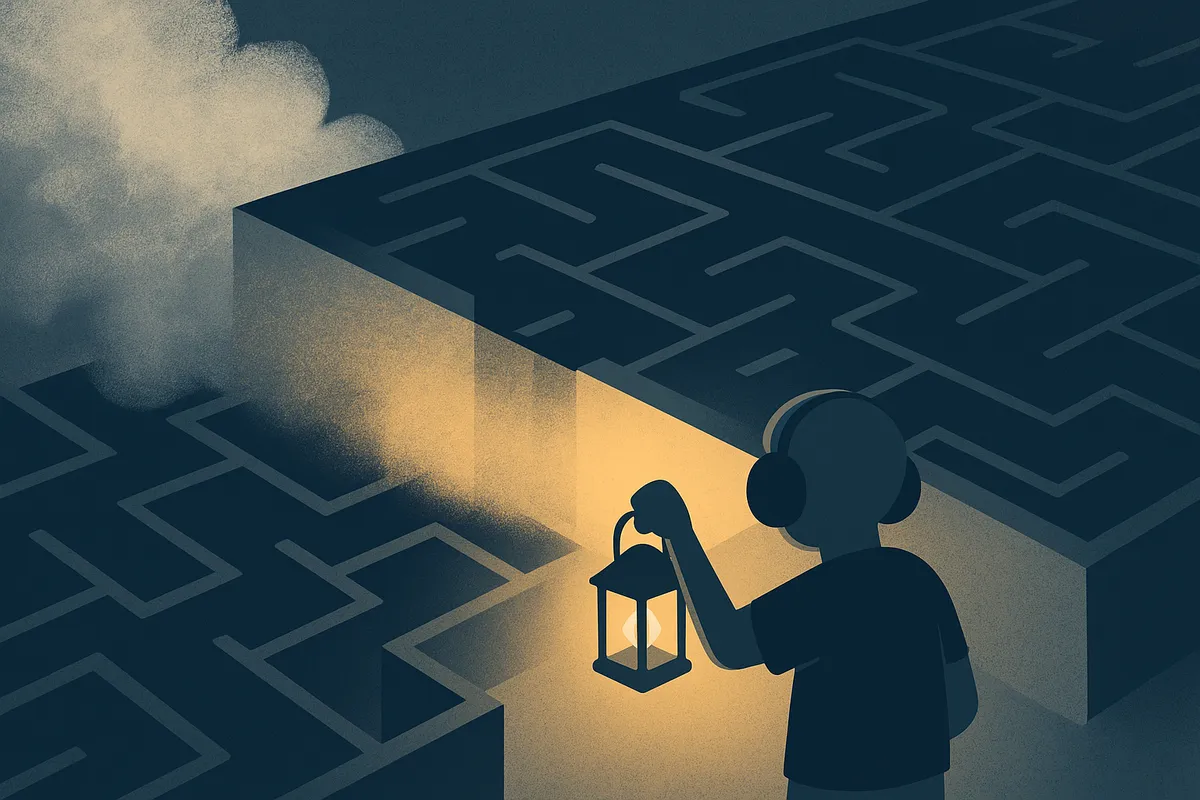

Evidence clears a path, but the frame still walls us in

Evidence clears a path, but the frame still walls us in

When a new umbrella review lands in Nature Human Behaviour, it matters who it protects — and who it forgets.

A multi-university team (Paris Nanterre, Paris Cité, Southampton) reanalyzed 248 meta-analyses covering 200 trials with more than 10,000 participants. The verdict was clear: no complementary or alternative treatment for autism is supported by high-quality evidence. Safety? Rarely measured. Fewer than half of the therapies included any tolerability or side-effect assessment (Gosling et al. 2025).

That clarity matters. Families who are desperate for help are often steered toward expensive interventions with glossy promises. This study pulls the curtain back: some interventions show apparent benefits, but the evidence behind them is very low quality and not reliable enough to guide practice.

Plain Language Summary

- Scope: Reviewed 248 meta-analyses of 200 trials with 10,000+ autistic participants.

- Finding: No CAIM intervention has reliable, high-quality evidence of effectiveness.

- Nuance: Some interventions (music therapy, animal-assisted therapy, melatonin, rTMS) showed large effect sizes, but the evidence was very low quality. Only oxytocin in adults (small effect on repetitive behaviours) and fatty acids in children (safety, not efficacy) reached moderate-quality evidence.

- Safety: Rarely studied; less than half of interventions measured adverse effects. Melatonin showed no increase in adverse events, though the evidence was still rated very low.

- Examples: Acupuncture, music therapy, probiotics, vitamin D and herbal medicine.

- Resource: An open-access online platform (EBIA-CT) now maps the evidence for families and clinicians.

Credit where it is due: the authors, Corentin J. Gosling et al, made two rare, harm-reducing moves. First, they explicitly used identity-first language (“autistic individuals”) and noted that this reflects community preference. That choice is unusual in mainstream journals and worth naming. Second, they built an open-access evidence platform so families and clinicians can see the data for themselves. Transparency matters, and this is a constructive step.

But the frame remains intact. The research still describes autism as “impairments in communication and social interaction” with “restricted, stereotyped and repetitive behaviours.” Autistic life is the object, not the subject. The findings protect families from wasting money — but they don’t ask what supports autistic people actually want or how “safety” feels when measured by autistic bodies rather than clinical checklists.

The harm mechanism is subtle: medicalization as default. The beneficiaries are researchers publishing null results and parents warned away from snake oil. The ones still erased are autistic people, whose well-being is not measured on our own terms.

There’s another layer worth naming: the persistence of treatment-first research agendas. Even when studies find no intervention is reliably supported by strong evidence, the question being asked is still “what might treat autism?” instead of “what would improve autistic lives?” That question pulls funding, shapes outcomes and defines credibility. It also ensures that autistic well-being remains measured only in terms of “symptom reduction,” not agency or joy.

So the study clears fog, yes — but it leaves the frame untouched. The question isn’t whether acupuncture or vitamin D work. The question is why autism research still begins by asking what will “treat” us instead of asking what will help us live.