Noora: The AI That “Teaches” Autistic People Empathy and the Old Myth It Recycles

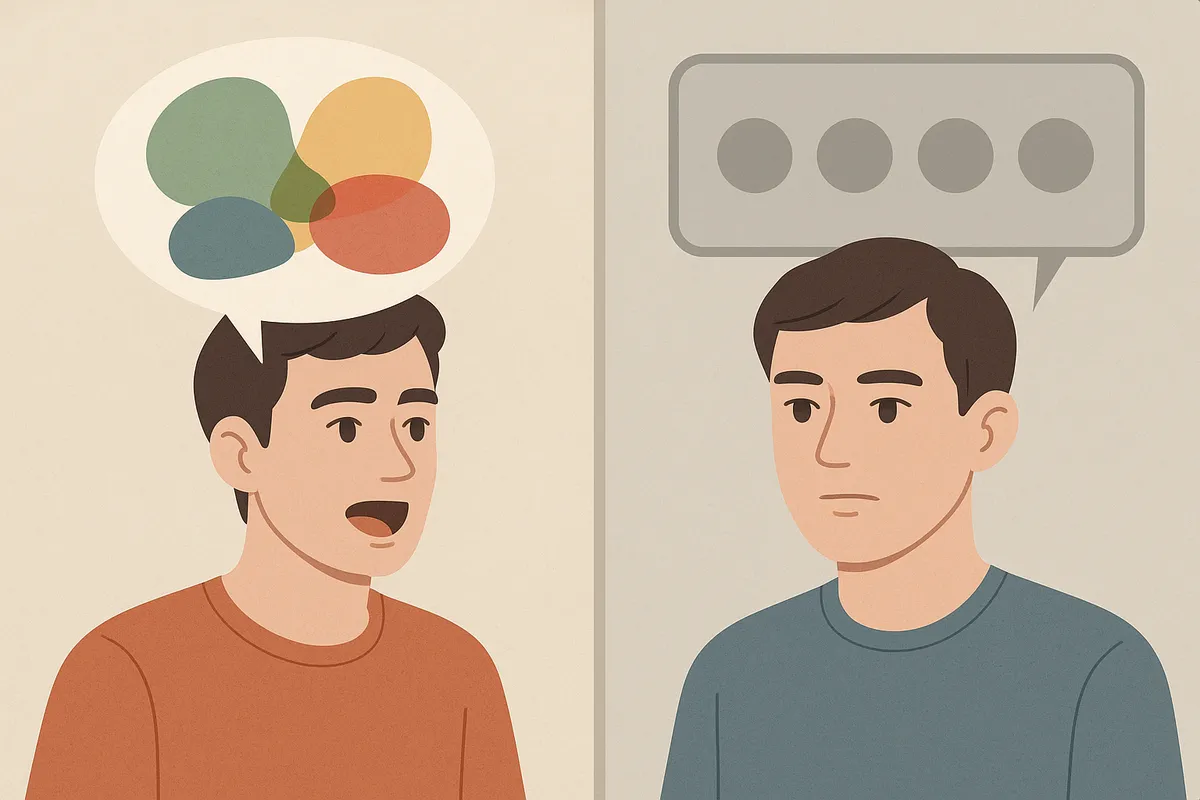

When AI teaches only one side to “empathize,” what gets lost is the conversation itself

When AI teaches only one side to “empathize,” what gets lost is the conversation itself

Stanford just ran a randomized controlled trial on a chatbot called Noora. They published it in Journal of Autism and Developmental Disorders and then their own HAI press office put out a headline that reads like it was written twenty years ago: “An AI Social Coach Is Teaching Empathy to People with Autism.” If you have any history in autism research you’ll know exactly what’s wrong with that sentence. It assumes a gap to be closed. It assumes empathy means a very specific set of neurotypical conversational signals and it quietly assures the reader that, don’t worry, science is on the case — autistic people are being fixed.

The study itself is less sensational but it carries the same frame. Thirty autistic people age eleven to thirty-five were pre-screened so that only those who scored below 60% on the researchers’ empathy test got in. That’s deficit-framing for that subgroup, though not a claim about all autistic people. Then half used Noora for about two hundred short drills over four weeks. Noora works like this: it gives you a “safe” pre-written statement, you tag it as positive, neutral or negative, you respond and it grades you. If you match its idea of empathy you get praise and even confetti on your screen — added after pre-trial testers specifically requested it. If you don’t it tells you why you’re wrong and shows you a “model” answer. These model answers were crafted by the research team; in my reading, the tone and examples align with mainstream U.S. conversational style, though the paper does not explicitly define them that way.

By the end the Noora group’s “empathy scores” in a scripted human conversation rose from about seventeen percent to fifty-one percent. The control group stayed the same. The authors call this a big success and within the scoring system they designed it is. But here’s what they didn’t measure: whether any of these changes made conversations feel better to the autistic participants. Whether their conversation partners actually understood them more. Whether this new skill made them less lonely, more connected, more respected. In other words, whether the empathy went both ways.

The press release framing doesn’t touch any of that. It repeats the setup — autistic people struggle with empathy, AI can help — as if the “double empathy problem” didn’t exist in the press framing, not in the paper’s discussion. The paper itself does discuss the double empathy problem at some length in the discussion section, but it does not appear in the operational definitions or outcome measures. When you define empathy only one way and then train us to perform it on command you’re not bridging a gap, you’re teaching mimicry. That one-way design can feel like assimilation, even if the study itself doesn’t use that language. And when you broadcast the work as “autistic people learning empathy” you reinforce the stereotype that autistic communication is inherently deficient.

This isn’t just an academic quibble. JADD is the flagship autism research journal. Stanford HAI is a global PR machine for AI. Together they’ve put a narrow, deficit-oriented frame in front of thousands of clinicians, educators, parents and policymakers. The next time a school district or employer buys “autism AI training” it will be this model they’re buying — a one-way adaptation program graded by neurotypical comfort sold as kindness.

It’s possible to imagine a different Noora. One that trains both sides of the conversation. One that treats autistic empathy — which often looks different but is no less real — as equally valid and teaches neurotypical people how to see it. One that uses autistic-authored model answers and lets participants decide which style they want to practice. That would still be AI-driven skill-building but without the one-way adaptation baked in.

For now this trial is a proof of concept for something narrower. It shows that AI can get autistic people to hit a specific conversational target. What it doesn’t show is whether that target leads to mutual understanding or just a higher score on a test we didn’t design. And until the definition of empathy changes studies like this — and their PR headlines — will keep telling, in my opinion, a very old, very wrong story about us.