Hugging Robots And The Friendships We Refuse To Build

Moffuly-MS image courtesy of study authors

Moffuly-MS image courtesy of study authors

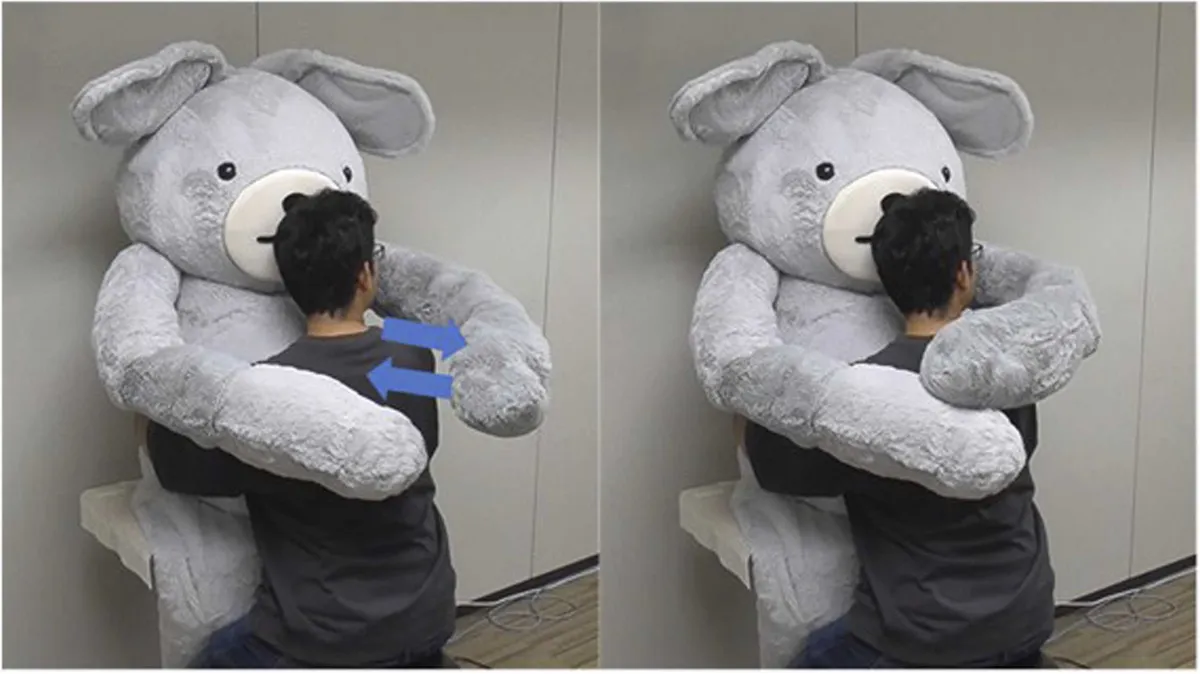

A study by Kumazaki and colleagues (2025) dropped into the Asian Journal of Psychiatry with the kind of framing we rarely see in autism research. Not a cure claim. Not a deficit tally. Instead, a test: what happens when autistic adults interact through a teleoperated hugging robot? The machine, named Moffuly-MS, towers two meters tall with oversized plush arms. Twenty-four autistic participants paired up across six days, alternating roles. One operated the robot to give a hug, the other received. Then they switched. The point was not compliance or correction but friendship.

Friendship As Method

For decades, interventions like PEERS® have promised “social skills” gains but fallen flat when it comes to actual relationships. This study acknowledges that gap. The question asked is not “how do we train autistic people to act more normal” but whether reciprocal, mediated touch could lower anxiety enough to let connection form. Participants reported more knowledge of their partner, more sense of oneness, and more relaxation in the hug condition compared to without. Importantly, autistic self-report was treated as reliable data rather than filtered through caregiver interpretation. That alone marks a small framing shift.

The Edges Of Inclusion

And yet the old machinery still shows through. Eligibility required DSM-5 confirmation by a psychiatrist, DISCO diagnostic interviews, IQ testing and exclusion of anyone on medication. The result is a narrow slice of autistic life — young adults, mostly male, mild to moderate traits, able to perform lab-based conversations. Those who need friendship most are once again screened out. The robot becomes a friend only for the already acceptable autistic subject. Structural exclusion rides along with the oversized plush arms.

Why A Robot And Not A Room?

The appeal of Moffuly is obvious. For autistic people who experience sensory overload, direct interaction can be exhausting. A mediated channel lowers the stakes. The hug is big, predictable, even comforting. But the existence of the robot is also an indictment. If society built spaces where autistic adults could gather without pressure, without judgment and with control over sensory input, would we need a two-meter teddy bear? The robot works for us because the world still doesn’t.

Reciprocal Design Worth Keeping

One part of this experiment deserves more attention: reciprocity. Every participant both gave and received the hug. No one was locked into the role of passive recipient. This matters. Autistic people are too often studied as objects of intervention rather than partners in exchange. Designing for alternation, for turn-taking, for agency, flips that script. Even if the mechanism here is a machine, the principle can travel: what if schools, workplaces and therapies built reciprocity into their DNA?

Better Questions Waiting

Instead of pouring resources into robot prototypes, what if funders backed autistic-led peer spaces that foster the same sense of safety and connection? Instead of medical gatekeeping on who counts as eligible, what if participation was defined by autistic adults themselves? If a plush robot can reduce anxiety in a lab, what could autistic-authored environments do in real life? The framing choice in this study opens a door. Whether the field walks through it or scurries back to deficit logic is the open question.

The Hug And The Mirror

This is not cure research. It is not prevention. It is not compliance-first. That alone earns it praise. But the hug robot also reveals a harsher truth: autistic adults have to rely on machines for gentleness because society withholds it. Until autistic-led design sets the terms of friendship, the biggest gift of Moffuly is not the hug it delivers but the mirror it holds up to a world still unwilling to embrace us.