Before the Data: Where Autism Research Goes Wrong

How to Audit an Abstract for Harm

How to Audit an Abstract for Harm

Most people think they already know what autism means. Many believe autism is one thing, when it’s actually a broad set of diverse experiences. Others picture a single image from television or news coverage. These assumptions deserve to be unpacked early so new readers can see why framing matters. They’ve heard the language of symptoms and severity, seen documentaries about lost potential, and read articles about “rising cases.” This is the lens the public inherits from decades of medical storytelling. It teaches us to see autistic people as puzzles, not participants — as data points waiting to be corrected. That same framing runs quietly beneath academic research, shaping what counts as knowledge long before any experiment begins.

How Scientific Writing Shapes Belief

For readers unfamiliar with how research writing works, an abstract is the short summary that appears at the top of every academic paper. It tells you what the study is about. It also explains what it found and why it matters. But most importantly, it quietly teaches you how to think about the subject. To someone new to the topic, autism research may seem like any other scientific field — a steady effort to understand human variation. Yet for decades, its dominant language has assumed that autistic people are damaged versions of someone else.

This framing took shape through diagnostic manuals like the DSM-III (1980), published by the American Psychiatric Association, which first included autism as “Infantile Autism,” and its later versions DSM-IV and DSM-5, which defined autism as a pervasive developmental disorder to be measured, treated, and managed rather than understood. Their language set the template for nearly all later research summaries. The most common words in its abstracts — deficit, impairment, disorder — carry quiet but lasting consequences. They position autistic life as something to correct rather than something to understand. This deficit framing shapes research questions, treatment models, and even public policy.

Why AAB Reads the Sentences Themselves

The Autism Answers Back (AAB) project treats language as data. We ask what happens if you take the same research but change the starting point — altering the lens that determines what kind of science is possible. The exercise below walks line by line through a single study, showing how small linguistic shifts change the entire meaning of the work. AAB’s sentence-by-sentence method exposes that structure by rewriting each line to show how language builds and sustains the deficit frame. What follows isn’t about style; it’s about ethics. When you change the grammar, you change the world the study describes.

Sentence by Sentence: How Deficit Language Builds a Study — and How We Take It Apart

Here we go. Let's rewrite the abstract from a paper titled "Large language models for autism: evaluating theory of mind tasks in a gamified environment" by Poglitsch et al., 2025, Scientific Reports, to test our hypothesis.

Original: Autism Spectrum Disorder often significantly affects reciprocal social communication, leading to difficulties in interpreting social cues, recognizing emotions, and maintaining verbal interactions.

Rewrite: Autistic and non-autistic people experience communication through different sensory and interpretive logics, which can create friction in mutual understanding.

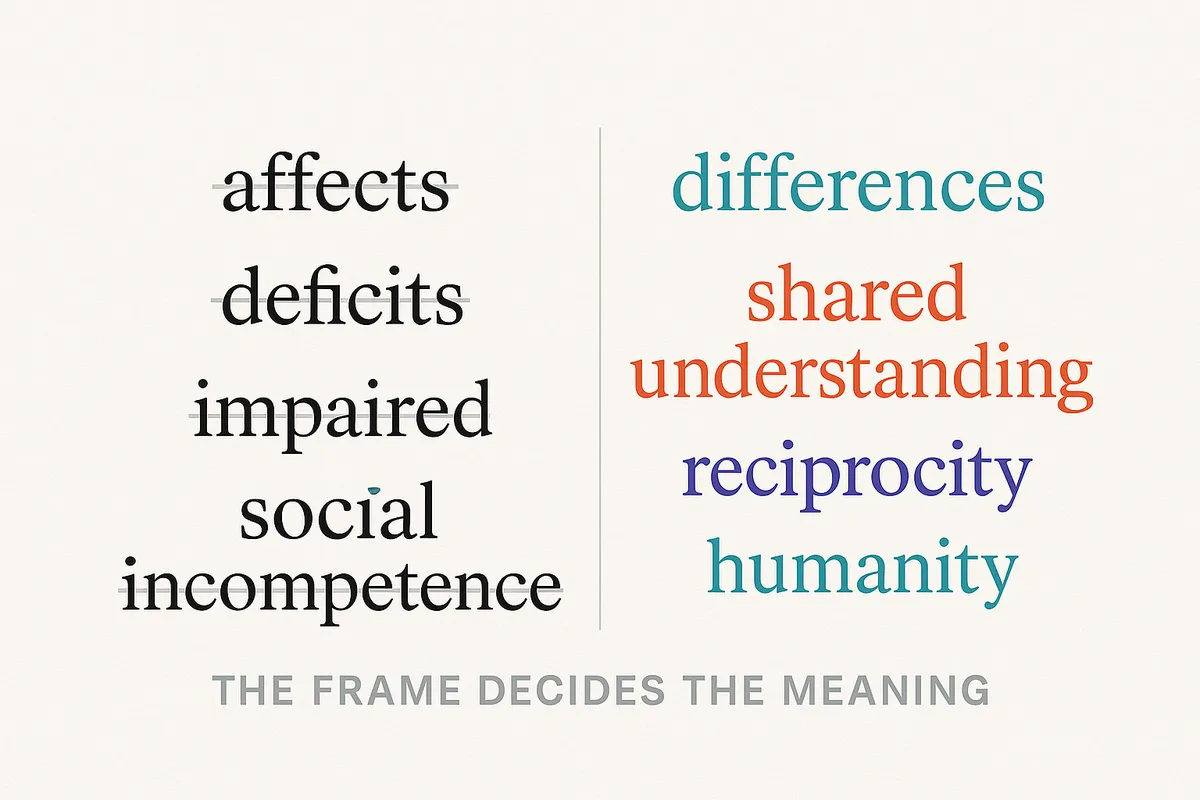

Comment: The first sentence sets the frame for everything that follows. In the original, autism affects something normal — a problem to be mitigated. In the rewrite, difference replaces deficit. The subject gains equality and agency; friction replaces failure.

Original: These challenges can make everyday conversations especially demanding.

Rewrite: These differences can make conversation unpredictable and sometimes exhausting for everyone involved.

Comment: The deficit frame narrows the challenge to autistic people alone. The rewrite makes the social space shared and relational — conversation as mutual navigation, not pathology.

Original: To support autistic people in developing their social competence and communication abilities, we propose an interactive game specifically designed to enhance social understanding.

Rewrite: To explore how technology might support shared understanding across neurotypes, we designed an interactive game that analyzes patterns of reasoning in social scenarios.

Comment: The original assumes autistic people lack competence and need training. The rewrite focuses on mutual comprehension. The goal changes from normalization to translation.

Original: By incorporating gamification elements and a user-centered design approach, the application aims to balance clinical relevance with high usability, ensuring it remains accessible, engaging, and beneficial for anyone seeking to improve their social skills.

Rewrite: The design uses game elements and user feedback to keep the experience accessible, engaging, and relevant for participants from different communication backgrounds.

Comment: Removing the word clinical shifts the moral axis of the work. It becomes participatory technology, not therapy. The audience broadens from patients to people.

Original: Large Language Models have recently been assessed for their ability to detect sarcasm and irony within Theory of Mind tasks, showing performance comparable to that of trained psychologists.

Rewrite: Large language models have recently been used to evaluate subtle forms of communication such as irony and implied meaning, performing comparably to human experts.

Comment: The technical claim remains, but the rewrite removes hierarchy. “Trained psychologists” is replaced by “human experts,” flattening power and reducing clinical authority.

Original: However, a significant limitation remains: their dependence on traditional “black box” AI architectures, which often lack explainability, interpretability, and transparency.

Rewrite: Yet these models still depend on opaque AI architectures, raising ethical questions about transparency and accountability.

Comment: A simple shift: from technical shortcoming to ethical concern. The rewrite points to values rather than engineering flaws.

Original: This limitation is particularly concerning when people with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder use these models to learn and practice social skills in safe, virtual environments.

Rewrite: This concern deepens when people across neurotypes use these systems to explore social reasoning in virtual spaces meant to be safe and inclusive.

Comment: “Learn and practice social skills” implies correction. “Explore social reasoning” implies curiosity and equality. Inclusion replaces remediation.

Original: This study investigates and compares the performance of Large Language Models and human experts in evaluating Theory of Mind tasks, providing a detailed comparative analysis.

Rewrite: This study compares how large language models and human experts interpret participants’ responses to social reasoning tasks, examining where alignment and bias emerge.

Comment: The final line turns measurement into reflection. The focus moves from testing autistic deficit to testing system fairness.

Closing Reflection

By rewriting one abstract sentence by sentence, we can begin to see that the harm isn't necessarily in the data or design but in the opening assumptions. A single word like affects or deficits predetermines who gets to be whole and who needs to be “fixed.” Reframing the same study through respect and reciprocity doesn’t erase the science — it exposes that the science has always been possible, just not ethical until the frame changed. It can be — once autism research decides that respect, not correction, is the starting point.