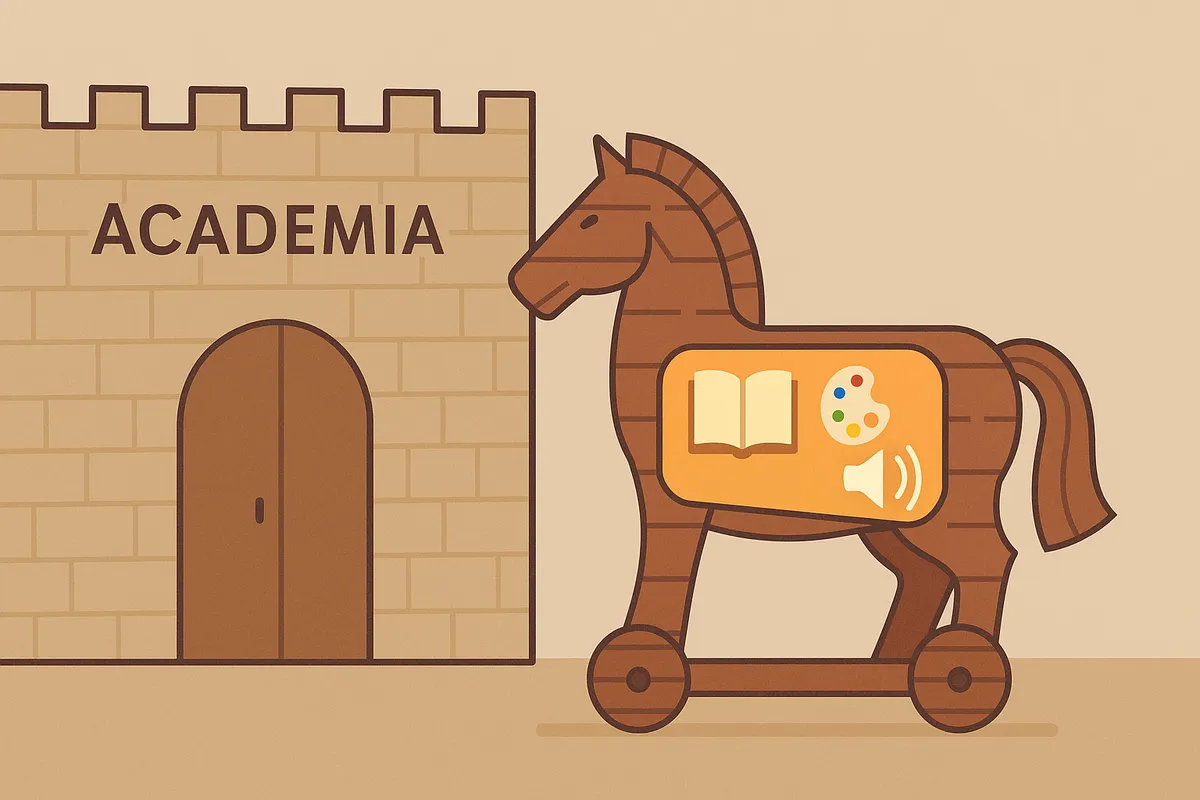

Autistic Students Smuggled a Trojan Horse Into the Academy

When autistic students speak, deficit walls begin to crumble

When autistic students speak, deficit walls begin to crumble

Academia doesn’t make it easy to tell the truth about autism. To survive peer review, you learn to package ideas in deficit-shaped language: “supports,” “accommodations,” “transition.” But every so often autistic scholars slip something more dangerous through — a question so obvious it threatens the whole frame: What if we listened to autistic students and focused on their strengths?

What Students Said

Sixteen autistic adolescents in Australia described how school feels when teachers actually understand them, when their interests shape learning and when their futures are taken seriously. Their accounts, published in Autism, showed that clarity and consistency could reduce stress and increase security, while interest-based learning kept engagement alive. They built friendships through strengths rather than rigid social rules. They wanted career guidance to start early, not as a panicked afterthought at graduation. None of this sounded like “special treatment.” It sounded like education that works once you stop reducing students to their diagnosis.

The Frame Under Pressure On the journal page (Autism), the study in question looks like yet another inclusion study. Safe academic words everywhere: “phenomenological methodology,” “accommodations,” “transition planning.” But inside the data is a refusal of normalization: autistic students are not asking to be fixed, they are asking to be recognized. The accompanying *C*onversation piece by the study's authors drops the mask: stop focusing on diagnosis, start listening to strengths. That isn’t just pedagogy. That’s long overdue sabotage — of the deficit frame itself.

Winners and Losers

Schools that keep diagnosis and normalization at the center benefit when autistic narration is ignored. Autistic students are harmed when strengths are erased and their futures narrowed to “support needs.” Yet this study proves that subversive truths can occasionally slip through academia's pathology-first frame. When an autistic author get work like this past peer review, it is thought leadership that forces the field to catch up.

Methods as Resistance The lead author, Jia White, is autistic. That changes the balance. Students weren’t specimens; they were narrators. Their words weren’t translated into deficits; they were published — and then echoed in public commentary — as counter-frames. That’s not methodology as usual. That’s methodology as resistance. Which raises the next question: if resistance is possible inside peer review, what would it look like if education research itself changed its frame?

Better Questions

What if all education research treated autistic narration as authoritative, not supplemental? What if future-focused planning and transition to adulthood started with autistic imagination, not labor-market compliance? What if clarity was universal design, not a concession?

What if strengths were baseline, not add-ons?

The Hard Truth What we are witnessing here is a message tucked inside the Trojan horse of peer review: autistic students are not diagnostic problems. They are subjects with strengths, futures and narration. Academia may only let that truth slip through in coded language — but we know what it is.

Autistic strengths. Smuggled past enemy lines.