A Panel of Autism Experts Responded to Trump. Here’s What They Missed.

Moving Beyond the Moment When Buffoonery Received the Presidential Seal of Approval

Moving Beyond the Moment When Buffoonery Received the Presidential Seal of Approval

For decades autism has been treated as a diagnostic container. The fights were about labels, prevalence numbers, and whether services should be expanded or restricted. That was familiar terrain. But the dangerous, ignorant announcement President Trump and Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. subjected the world to this week was something else: a deliberate revival of vaccine myths, mother-blame around Tylenol and talk of prevention. It was buffoonery on the surface, but buffoonery with a presidential seal carries danger. When state power turns conspiracies into press-room talking points the ground itself shifts. Autism is no longer a specialized subject for researchers and advocates. It has become a stage for national political theatre.

Into that breach stepped four voices in a New York Times Opinion panel: Helen Tager-Flusberg, Alison Singer, Brian Lee and Eric Garcia. They were not neutral stenographers. They repudiated the president’s claims with clarity. They reminded readers that association is not causation. They refused to re-litigate vaccines. They named the cruelty of telling mothers they should have toughed it out. For that, they deserve praise. In a moment where spectacle threatened to crowd out reason they anchored the discussion back in science and lived experience.

Praise Where It Belongs

Garcia in particular offered a reminder that cuts through policy chatter. When Trump recounted a story about a boy who was “lost” to autism after a vaccine, Garcia said plainly: that boy still exists. He still has a life worth fighting for. That kind of intervention matters because it re-centers autistic people as subjects not symbols. Lee, for his part, underscored that the data on acetaminophen collapses under sibling-control analysis. Association disappears when genetics are accounted for. Tager-Flusberg named the day “the most unhinged” discussion of autism in her career. Each of these interventions chipped away at the fog of misinformation.

In a climate this volatile even modest corrections are protective. To tell parents that autism is not a crisis but a difference, to remind them that prevalence increases reflect awareness and diagnostic change, is no small thing. The panel did not let Trump’s claims stand uncontested. That deserves acknowledgment.

The Limits of Subtypes

But within that same panel a deeper question surfaced. Alison Singer argued that the umbrella of Autism Spectrum Disorder has become so broad it is meaningless. Her proposed solution: return to subtypes such as classic autism, Asperger’s, and profound autism. On its face this looks practical. Services do differ. Support needs vary widely. Clinicians and policymakers want categories they can act on.

Yet history tells us that subtyping does not clarify so much as stratify. Asperger’s was once held up as the autism that could pass — quirky, high-functioning, even marketable. Classic autism, by contrast, was coded as tragedy. When the DSM-5 collapsed these categories into a spectrum it did not erase the fault line. It pushed it underground (What Was Lost When Asperger’s Was Absorbed). Autistic people still feel its effects in access decisions and social attitudes. To simply resurrect “profound autism” as a diagnostic category risks cementing those hierarchies all over again.

Singer’s concern is real. Families and service systems need ways to distinguish levels of support. But the answer is not to dig up the old categories. It is to build frameworks that reflect real variation without imposing hierarchies of legitimacy.

What AAB Has Already Proposed

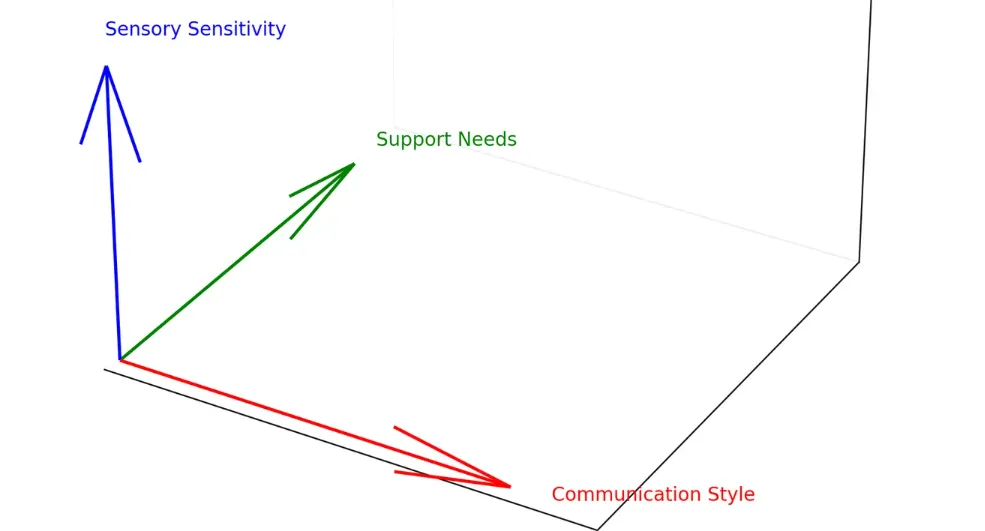

Autism Answers Back has argued for a different reframe: the autistic neurotype. Instead of a one-dimensional spectrum or a set of subtypes, the neurotype model describes autistic people through multidimensional profiles. Communication, support needs and sensory sensitivity each form an axis. A person may be verbal but require daily assistance. Another may be nonspeaking yet mostly independent in daily living. These combinations cannot be captured by labels like Asperger’s or profound autism. They require profiles, not boxes.

The power of the neurotype frame is that it preserves access to support while discarding deficit logic. It recognizes autism as a way of processing the world, not a broken version of typical development. It separates difference from deficiency. Services are still delivered, accommodations still secured, but without pretending that autistic existence is tragedy.

This is not a euphemism. It is not branding. It is a correction. Words shape systems. The term “Autistic Spectrum Disorder” tells insurance companies and schools to see deficits first. The term “autistic neurotype” tells them to map support profiles and respect difference. That shift matters because it redirects the entire system’s gaze.

Between Buffoonery and Bureaucracy

The danger of the current moment is that while one hand waves conspiracies from the podium, the other hand reopens old categories in the name of clarity. Both moves endanger autistic people, though in different ways. Buffoonery legitimizes misinformation. Bureaucratic retrenchment risks hardening hierarchies. Neither addresses the actual question: how do we design systems that recognize autistic people as whole and varied while delivering the supports they need?

The autistic neurotype offers a way through. It avoids the trap of nostalgia for subtypes and the trap of spectrum flattening. It says: describe the person, not the category. Build supports around needs, not labels. Preserve access, discard stigma.

Closing Beat

A panel of experts repudiated the president’s disturbing announcement. That matters. It matters that mothers were defended against blame, that vaccine myths were rejected, that autistic existence was named as real and valuable. But if the ground underneath autism has shifted, we cannot afford to fight today’s misinformation with yesterday’s categories. The path forward is not profound autism versus Asperger’s. The path forward is a new frame — one that sees us as a neurotype, multi-dimensional, fully human, and here to stay.